Navy Crew Memories from Chuck Wilbur ’57 1

(Photo courtesy of Mary Haber)

A Sword in the Chain

Navy Heavyweight Coxswain Charles (Chuck) Wilbur ’57 passes his Navy sword to Navy Lightweight Coxswain Grace Albertson ’17 on 8 April 2017

How I Became a Navy Coxswain

I intended to play lacrosse at the Academy. I graduated from a school in Baltimore where lacrosse was dominant, and since the 4th grade I had been taught to handle a lacrosse stick. By the time I reached high school, a lacrosse stick was like an extension of my arm, and I had won three varsity letters in the sport.

But in the fall of 1953, at the start of Plebe year, when intramural battalion crew was in season, Ed Stevens ’54, who was coaching the Fourth Battalion crew, was looking for a cox’n and picked me because I was the smallest Plebe he could find. I had intended to spend the fall in out-of-season lacrosse, but quickly learned that a Plebe follows the orders of a First Class Midshipman.

So, I found myself seated in the stern of a crew shell. Ed Stevens was the stroke oar of the Navy crew which had won the Olympics in 1952 and had gone undefeated in every race since then. He began putting our battalion crew together by stroking it himself, sitting just 18 inches from me, telling me what to say and do as the cox’n. Of course, I could not have had a better coach than the greatest expert oarsman stroking a shell!

Ed was both a fine teacher and a very likable person. I truly enjoyed working for him and I learned a lot. Needless to say, I learned how to be a cox’n the correct way. I learned that a cox’n must be a contributor to the performance of the boat, not just helmsman and weight to be pulled around; and Ed Stevens taught me how to make a significant, positive contribution to that performance.

Ed did not participate as an oarsman in our battalion boat, he coached it—and we WON the battalion championship.

In the spring, when the choice came between lacrosse and crew, I went out for crew since I was at a disadvantage not having participated in out-of-season lacrosse in the fall. There were cox’ns who had prior experience, so I had no chance in making the first Plebe boat, but I participated and gained experience. The next year, I gained more, and I made up my mind that, if I was going to be a cox’n I would be the best one on the team.

On the Art of Rowing

Navy was fortunate to have Rusty Callow as head coach. Rusty was like a father to all of his oarsmen, and everyone loved him. Rusty was then known as the “Dean of American Rowing Coaches” because many of the other collegiate rowing coaches had been oarsmen under his tutelage, either at the University of Washington, where he won three Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championships in his first four years, or at the University of Pennsylvania, where he coached for twenty-three years.

When Rusty came to the Naval Academy, he was asked why he had made the change after so many years at Penn and so late in life. Rusty answered, “We didn’t have the water. The Schuylkill River silted up something awful—it was too thick to drink and too thin to plow.”

On another occasion he was asked if he would do it all over again. “Yes, Sir,” he answered, “Yes, Sir. You know, my brothers made a million dollars logging. But rowing, it’s more than just pulling an oar.” Then he compared rowing to golf. I heard Rusty make this comparison, myself. He said words to the effect that “just like a golfer has to hold his hands and feet correctly and move his body and his club perfectly as he executes his swing, an oarsman must similarly control his body and his oar in a perfect manner; but an oarsman must do it in perfect harmony with seven other oarsmen, and furthermore, must do it when utterly and totally exhausted.” I observed that as a cox’n. Crew is the ultimate in teamwork and the individual members of a successful crew will absolutely give their all rather than let down their teammates.

On Rhythm and Speed

At the 1955 Adams Cup Race, the Navy varsity heavyweight crew came in second to Penn, and this ended what would become known as the Navy varsity heavyweight crew winning streak of 31 unbeaten races.2 All the rowers from the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew had graduated by ’54, so this race was rowed by a new group of oarsmen.3 Thereafter, Rusty kept trying one combination of oarsmen after another in search of the fastest boat. I heard him say, time after time, “It isn’t the eight best oarsmen who make the boat go fastest, it’s the eight oarsmen who row best together.”

On one occasion just before that Adams Cup race against Penn and Harvard, Coach Callow pointed to the six-oar in the varsity boat, Lenny Anton ’56, whom he described as a 210 pound son of a Pennsylvania coal miner, and said that it was normal for such a big, powerful man to sit in “the engine room” (which he described as seats five and six); but, he also noted that Lenny was so smooth and perfect in his rhythm that he could stroke. Well, in order to prove his point, as well as to continue his search for the best combination of eight oarsmen to row the fastest boat, the next week Coach Callow put Lenny in the stroke seat. Although Navy did not win that day, Lenny did a fine job as stroke, and Coach Callow then continued his search for more speed. [Note: In the final race of the 1955 season, Navy would win the Western Sprints with Lenny Anton rowing stroke.]

Throughout the 1955 season and again during the regular 1956 season, Coach Callow had a difficult time finding “the eight oarsmen who row best together” as he shifted oarsmen from one boat to another and one position to another in order to make the boats faster. And, in the first race of the 1956 season against Princeton, Navy lost by a considerable margin.

On To The 1956 IRA National Championships

During the 1956 season, the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew returned to train on the Severn in an attempt to repeat their performance in the upcoming 1956 Olympic Games, so we had real competition in practice. As it so happened, the 1956 team captain, Willis (Will) Rich ’56, asked Coach Callow to make me the varsity cox’n and Coach Callow made it so, Thus, I had the opportunity to cox alongside the 1952 crew, which included stroke Ed Stevens ’54 [who had taught me to be a cox’n back in 1953]. This practice competition gave us a chance to really judge our performance as Coach Callow continued seat-racing, still trying to find those “eight oarsmen who row best together,” and while we were making progress, race results showed that we were still not up to the level of our opponents.

Then, after the regular season, there was an extended period between the Eastern Sprints and the IRA National Championships on Onondaga Lake. We were rowing twice-a-day against the 1952 Olympic crew—long distances in the early morning and in the evening—and it was apparent that we had made a significant improvement in the varsity boat with our final assignment of oarsmen.

When we lined up on Onondaga Lake at Syracuse, we were in the next to last lane on the left. Princeton was to our starboard, and MIT was to our port in the farthest left lane. We got off to a mediocre start, and Princeton was about three seats ahead of us when we finished our starting 25 and then lengthened to our normal stroke, which was about 31 for a three mile race.

We had only gone about another twenty strokes when I heard the Princeton cox call for a Big Ten. I thought this was strange and premature since his crew was still tired from the start and had only just reached their regular racing beat—why a Big Ten? Well, using a bit of coxswain psyops, which of course the Princeton cox would hear, I called out to my oarsmen that Princeton was going to take a Big Ten and added, “DON’T LET THEM GAIN ANYTHING.” Our oarsmen really put their backs into it and when Princeton’s ten strokes were over, Navy had GAINED a seat on Princeton. However, I knew that since we were so close together neither crew knew exactly how far ahead one or the other boat was, so I yelled to my men that “PRINCETON TOOK A BIG TEN AND WE GAINED TWO SEATS!”

Of course, I was fibbing, but only Princeton’s cox could know. And, my crew could see that the boat to port was over half a length behind us already. Then I told my crew, “OK. IT’S OUR TURN. LET’S TAKE OUR BIG TEN AND SHOW PRINCETON HOW IT’S REALLY DONE. READY! TEN, NINE….” By the time I had counted down, we had gained about five seats on Princeton, and my oarsmen could plainly see Princeton falling behind. Talk about motivation.

Then I looked across the water to starboard and picked out some other boat. I yelled out to my crew, “Alright, we’ve passed Princeton. Now we’re alongside Wisconsin. Let’s pass them. We’re moving up on them. We’ve gained two seats on Wisconsin. Now I’m alongside Stanford. Let’s pass Stanford. Reach out. I’m two seats up on Stanford. Now we’re four seats up on Stanford.”

We had gotten off the line nearly eighth or ninth out of the twelve boats in the race, and I identified each boat to starboard as we came up alongside it. Sometimes, I was guessing as to which college it was, but that didn’t matter, I told my crew some name, and they responded accordingly. As we progressed along the 3-mile course, we simply walked by one boat after another until only Cornell was ahead of us, but we simply ran out of room to catch them. As everyone knew going into the championship, Cornell had been the crew to beat, and we very well might have done so, too, but we just ran out of water.4, 5 The race results were: 1-Cornell (16:22.4), 2-Navy (16:31.5), 3-Wisconsin (16:34.7), 4-Washington (16:34.9), and 5-Stanford (16:37.1); unfortunately, the order of finish for the remaining seven crews is not recorded in Navy’s Race Report.

As we paddled to the seawall I could see Coach Callow on the head of the pier. The course on Onondaga Lake ends at a seawall with large lane markers on high signs, and Coach Callow was jumping up-and-down and laughing! He was so giddy and happy. He had indeed finally found his “eight oarsmen who row best together” to make our boat go fastest.6 And we were runner-up national champions.

The 1957 Princeton Race

Our first race of the 1957 season was at Princeton. The beating they had given us the previous year on the Severn—as well as the 1956 IRA where we accelerated away from them and gave our crew such motivation—were both vivid in my mind. Only one oarsman in the boat remained from the 1956 IRA crew.

Princeton has a perfect race course. It was built and paid for by Andrew Carnegie.7 The course has straight lanes that are well-marked by buoys, and it has a road parallel to it so people can drive along and follow the race. There is also a large area for spectators at the finish.

At the start, both of our crews were neck-and-neck—within a seat of each other. All the way down the race course, neither boat got more than one seat ahead of the other. Neither cox’n called for a Big Ten, as every oarsman was pulling his hardest with every stroke; and I realized that nothing could be gained by asking for anything more. I had never raced here before and was wary of falling short of the finish, so I called for my final 20 strokes one stroke later than I otherwise would have. I first told my men that this was it—they had to win the race on the final 20 strokes. In that last 20 strokes, we moved ahead by about 18 inches to win the race as we crossed the line on my count of two. The official time for the race was 8 minutes and 45 seconds to 8:45.1—a difference of only one-tenth of a second over three miles. This must be the closest three mile race ever rowed.

We had to rest about ten minutes before we could turn around and row back to the boat house, as the oarsmen were simply too exhausted. This was the only race where I felt sorry for the other boat, for they had rowed just as hard as our crew, and come up short.8

Notes

1 Editor’s Note: Charles Harrison “Chuck” Wilbur ’57 coxed Navy heavyweight eights from 1953-1957, and coxed the 1956 and the 1957 Navy varsity eights (MV8+).

2 Regarding the Navy varsity heavyweight crew win streak, at the time, Navy rowers counted the number of victories as much higher—something like 38—because they counted the heats that the crews won as well as the finals. Remarkably, the 1952 Olympic boat with eight oarsmen who rowed together from 1951-1954 is said to have never trailed in any final or qualifying heat during their win streak.

3 Although upon the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew’s return to the U.S. from Helsinki Life magazine had already dubbed them The Great Eight, in Hubbard Hall, the crew was always known as the Olympic Crew.

4 Beginning in 1898 and running through 2002 Yale and Harvard did not row in the IRA National Championship because of scheduling conflicts with their Harvard-Yale Regatta. And, although Yale had upset heavily-favored Cornell in their annual Carnegie Cup Regatta on the Housatonic River, one week later Cornell beat Yale at the 12 May 1956 Eastern Sprints, which is why Cornell was favored in the 1956 IRA.

5 Just before the July 1956 U.S. Olympic Trials, one of the members of the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew fell while playing Frisbee and broke his wrist. I can tell you from our practice-racing against them just before we finished second to Cornell in the IRA that that Olympic Crew was once again VERY FAST—much faster than our varsity. I truly believe they would have won those Trials if they had not had to row with a substitute. Yale won the Trials with a winning time of 6:33.5 followed by Cornell 6:36.2, Navy’s Officer Crew 6:37.5, Washington 6:37.8, and Wisconsin 6:40.8. Yale went on to win the 1956 Olympics too.

6 The Navy varsity heavyweight boating for the 1956 IRA was: Bow– Willis Scott Rich ’56;

2– Garland Ottis Audilet ’56; 3– Charles Franklin Coker ’56; 4– Moston Robert Mulholland, Jr. ’58; 5– Craig Luther Barnum ’57; 6– Leonard George R. Anton ’56; 7– John Wayne Forbrick ’56; Stroke– John Lawrence Nulty, Jr. ’58; Cox– Charles Harrison Wilbur ’57.

7 Regarding the Princeton course, Andrew Carnegie was having his portrait painted and the painter began discussing Princeton crew, of which, Carnegie was a fan. The painter lamented the fact that Princeton did not have a suitable venue for racing. He then mentioned that there was a swampy area on part of the campus which could be dammed and dredged to make a suitable race course. After some lengthy persuasion, Carnegie agreed to fund the building of the race course. However, one result of the damming was the flooding of a road which necessitated the construction of an expensive bridge which the state insisted be built at Carnegie’s expense. At the opening ceremony of the race course, the President of Princeton, then Woodrow Wilson, asked Andrew Carnegie to build a building for the University on some of the now dry land. Carnegie’s reply was, “I have just given you an expensive race course.” Wilson’s response was, “I ask for bread; you have given us cake.”

8 The Navy varsity heavyweight boating for the 1957 Princeton race was: Bow- Robert Taylor Scott Keith, Jr. ’58; 2- Dennis Young Sloan ’57; 3- Thomas Henry Bond ’59;

4- Moston Robert Mulholland, Jr. ’58; 5- Keith Lawrence Christensen ’59; 6- Grant David Wright ’59; 7- John Naeve Pechauer ’59; Stroke- Guy Haldane Curtis III ’59; Cox– Charles Harrison Wilbur ’57.

Addendum

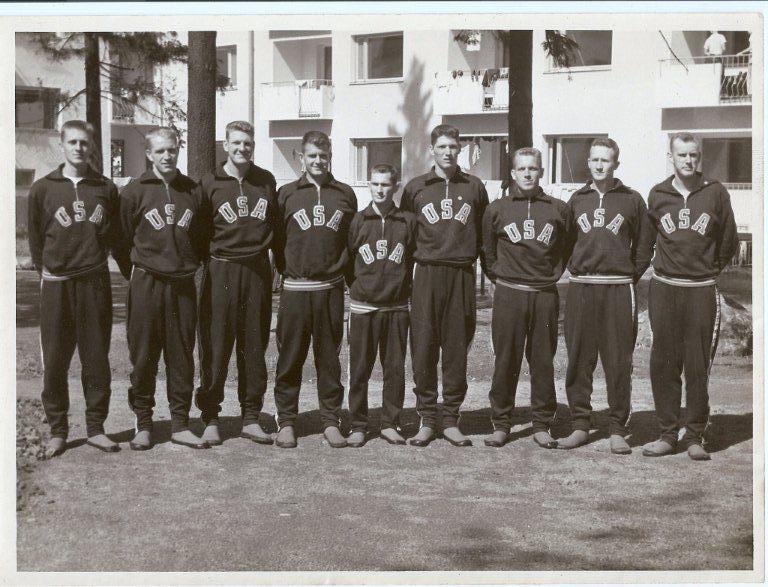

(Photo courtesy of Naval Academy Athletic Association)

The 1953 Great Eight with a new coxswain—Dave Manring graduated in 1952

L-R: Stroke- Edward G. Stevens, Jr. ’54; 7- Wayne Thomas Frye ’54; 6- Henry Arthur Proctor ’54; 5- Robert Milan Detweiler ’53; Cox- Robert William Germany Jones ’53; 4- Richard Frederick Murphy ’54; 3- James Ralph Dunbar ’55; 2- William Beauford Fields ’54;

Bow- Franklin Bradford Shakespeare ’53

Navy’s Varsity Heavyweight Eight Coxswains (1952 – 1954)

Three different coxswains coxed Navy varsity heavyweight eights during Navy’s 29-race win streak from 1952 – 1954.

Cox I was Charles David (Dave) Manring ’52 who coxed the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew.

Cox II was Robert William Germany (Bob) Jones ’53 who coxed the 1953 Navy Crew.

Cox III was William Arthur (Bill) Kennington ’55 who coxed the 1954 Navy Crew.

Dave Manring and Bob Jones would eventually return to the Naval Academy as Head Coaches of Navy Lightweight Crews.

1954 Navy Varsity Heavyweight Eight

Two rowers replaced Bob Detweiler and Frank Shakespeare following their graduation in 1953.

Bow- Willis Scott Rich ’56 (formerly Frank Shakespeare ’53)

2- William Beauford Fields ’54

3- James Ralph Dunbar ’55

4- Richard Frederick Murphy ’54

5- John Wayne Forbrick ’56 (formerly Bob Detweiler ’53)

6- Henry Arthur Proctor ’54

7- Wayne Thomas Frye ’54

Stroke- Edward G. Stevens, Jr. ’54

Cox- William Arthur Kennington ’55

Other Rowers in Navy’s Varsity Heavyweight Eight for a Few Races during 1952 – 1954

Five other rowers rowed in Navy’s varsity heavyweight eight for a few races during Navy’s 29-race win streak from 1952 – 1954.

1952

Bow- Albert Louis Villaret ’53

2- Lawrence Stuart Colwell ’54

6- Edward Reed Worth ’53

1954

Bow- Roger Frederick Scott, Jr. ’55

5- Russell Duane Hensley, Jr. ’55

An Interesting Anecdote

This story was related by William John (Bill) Hipple ’52 who was the manager of the 1952 Navy Olympic Crew.

After losing early in the 1952 spring rowing season Rusty Callow decided to seat a varsity boat of two Segundos and six Youngsters that was coxed by a Firsty.

Following this boating shake-up, one day during practice we were in the launch and I noticed Coach Callow was shaking his stopwatch and tapping it on his knee. He then threw it in the Severn and said, “That stopwatch doesn’t work, I’ll have to get another from my office.”

The next day at practice I noticed him tapping his stopwatch again—and once again he threw it in the Severn. This time he told me to go into Annapolis and buy a new stopwatch for the next day’s practice.

Well, the next day I brought Coach Callow a new stopwatch. During practice he just kept staring at that watch and finally he turned to me and said, “I can’t believe these times.”

So, somewhere buried under the muck and mud at the bottom of the Severn River are two stopwatches that before they went into the water had been working perfectly fine.

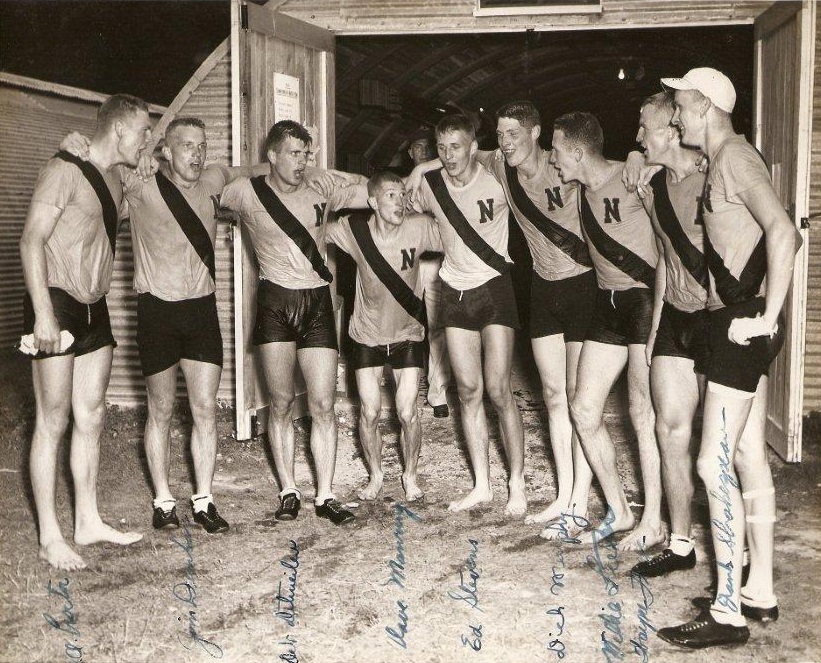

(Photo courtesy of Naval Academy Athletic Association)

The 1952 Navy Olympic Crew

L-R: 6- Henry Proctor ’54; 3- Jim Dunbar ’55; 5- Bob Detweiler ’53; Cox- Dave Manring ’52; Stroke- Ed Stevens ’54; 4- Dick Murphy ’54; 2- Willie Fields ’54; 7- Wayne Frye ’54; Bow- Frank Shakespeare ’53

Links of Interest